Scientists studying the brain have discovered that the organ operates on up to 11 different dimensions, creating multiverse-like structures that are “a world we had never imagined.”

By using an advanced mathematical system, researchers were able to uncover architectural structures that appears when the brain has to process information, before they disintegrate into nothing.

Their findings, published in the journal Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, reveals the hugely complicated processes involved in the creation of neural structures, potentially helping explain why the brain is so difficult to understand and tying together its structure with its function.

In the latest study, researchers honed in on the neural network structures within the brain using algebraic topology—a system used to describe networks with constantly changing spaces and structures. This is the first time this branch of math has been applied to neuroscience.

"Algebraic topology is like a telescope and microscope at the same time. It can zoom into networks to find hidden structures—the trees in the forest—and see the empty spaces—the clearings—all at the same time," study author Kathryn Hess said in a statement.

In the study, researchers carried out multiple tests on virtual brain tissue to find brain structures that would never appear just by chance. They then carried out the same experiments on real brain tissue to confirm their virtual findings.

They discovered that when they presented the virtual tissue with stimulus, groups of neurons form a clique. Each neuron connects to every other neuron in a very specific way to produce a precise geometric object. The more neurons in a clique, the higher the dimensions.

In some cases, researchers discovered cliques with up to 11 different dimensions.

The structures assembled formed enclosures for high-dimensional holes that the team have dubbed cavities. Once the brain has processed the information, the clique and cavity disappears.

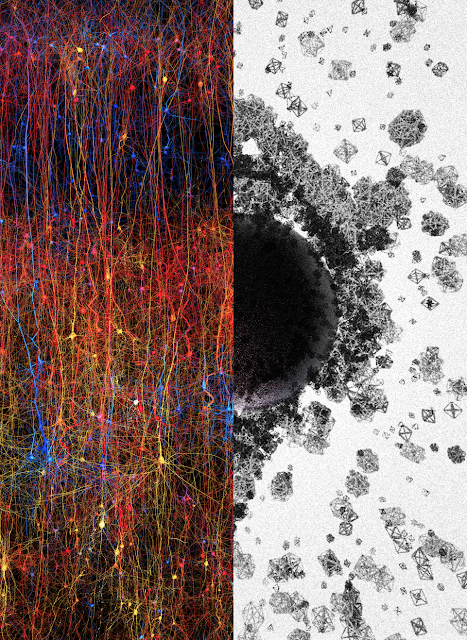

The left shows a digital copy of a part of the neocortex, the most evolved part of the brain. On the right is a representation of the structures with different dimensions. The black hole in the middle symbolizes a complex of multi-dimensional spaces, or cavities.

"The appearance of high-dimensional cavities when the brain is processing information means that the neurons in the network react to stimuli in an extremely organized manner," said one of the researchers, Ran Levi.

"It is as if the brain reacts to a stimulus by building then razing a tower of multi-dimensional blocks, starting with rods (1D), then planks (2D), then cubes (3D), and then more complex geometries with 4D, 5D, etc. The progression of activity through the brain resembles a multi-dimensional sandcastle that materializes out of the sand and then disintegrates," he said.

Henry Markram, director of Blue Brain Project, said the findings could help explain why the brain is so hard to understand. "The mathematics usually applied to study networks cannot detect the high-dimensional structures and spaces that we now see clearly,” he said.

"We found a world that we had never imagined. There are tens of millions of these objects even in a small speck of the brain, up through seven dimensions. In some networks, we even found structures with up to eleven dimensions."

The findings indicate the brain processes stimuli by creating these complex cliques and cavities, so the next step will be to find out whether or not our ability to perform complicated tasks requires the creation of these multi-dimensional structures.

In an email interview with Newsweek , Hess says the discovery brings us closer to understanding “one of the fundamental mysteries of neuroscience: the link between the structure of the brain and how it processes information.”

By using algebraic topology, she says, the team was able to discover “the highly organized structure hidden in the seemingly chaotic firing patterns of neurons, a structure which was invisible until we looked through this particular mathematical filter.”

Hess says the findings suggest that when we examine brain activity with low-dimensional representations, we only get a shadow of the real activity taking place. This means we can see some information, but not the full picture. “So, in a sense our discoveries may explain why it has been so hard to understand the relation between brain structure and function,” she explains.

“The stereotypical response pattern that we discovered indicates that the circuit always responds to stimuli by constructing a sequence of geometrical representations starting in low dimensions and adding progressively higher dimensions, until the build-up suddenly stops and then collapses: a mathematical signature for reactions to stimuli.

“In future work we intend to study the role of plasticity—the strengthening and weakening of connections in response to stimuli—with the tools of algebraic topology. Plasticity is fundamental to the mysterious process of learning, and we hope that we will be able to provide new insight into this phenomenon,” she added.

No comments:

Post a Comment