Shifting Out of Second: Spur the Effort

It may be tempting to believe that social media’s popularity outside the office will imbue efforts inside if the technology is right. Although there may be some initial enthusiasm, it can quickly vanish. To spur and maintain the adoption of social, companies need to nurture it in a systematic way. Businesses that are making the greatest progress toward becoming a socially connected enterprise focus rigorously on four interrelated areas: leading a social culture, measuring what matters, keeping content fresh and changing the way work gets done.

Leading a Social Culture

Although providing a tool may be a springboard for adoption, it is not enough. Company leaders must actively drive its use.

When Teva launched Radar to accelerate the resolution of supply-chain issues, for example, the project gained bottom-up traction because the tool added value to people’s jobs. However, whenever top management support faded, the effort quickly lost steam; with every change in top management, Jean-Francois found herself reaching out to the new leaders and bringing them on board in order to rekindle the momentum.

Furthermore, “[for] social collaboration to be successful in business, leaders have to explain the why,” says Michael Slind. “Leaders need to really collaborate and make sure people understand the importance of transparency, shared accountability — and sharing in general.” Connecting social with important business objectives is the crux of “explaining the why.”

Morgan Stanley’s Boyman, for example, credits the head of sales for connecting social to business needs and assuring that the bank became a social business leader in its industry. “If I didn’t have the head of our sales force tell me that we have to be the first in the industry to do this, it never would have happened,” says Boyman. “Even when the project hit initial bumps because of the realization it would require IT dollars, he was still committed to keeping people focused and getting the needed resources.”

Leadership also plays a pivotal role in creating a social business culture. American Express SVP Leslie Berland notes: “Does the company have leaders who are believers in what’s possible? That’s a big piece of the [social business] puzzle.”

Morgan Stanley’s Boyman, for example, credits the head of sales for connecting social to business needs and assuring that the bank became a social business leader in its industry. “If I didn’t have the head of our sales force tell me that we have to be the first in the industry to do this, it never would have happened,” says Boyman. “Even when the project hit initial bumps because of the realization it would require IT dollars, he was still committed to keeping people focused and getting the needed resources.”

Leadership also plays a pivotal role in creating a social business culture. American Express SVP Leslie Berland notes: “Does the company have leaders who are believers in what’s possible? That’s a big piece of the [social business] puzzle.”

At companies known for their social culture, such as Cisco and American Express, an open and collaborative culture is always in the room. “Cisco has a really open culture of transparency and trust,” says Jordan. “When you are working on driving successful business outcomes, you need to be in the middle of it with your colleagues, peers and customers at the personal level.”

Leslie Berland emphasizes the importance of American Express’s collaborative team-oriented culture and how critical it is to drive social business initiatives. “I think it’s impossible to win in digital or in social media if you’re approaching it in a siloed way. And you can see it when you see different brands and companies and organizations launching things in the social media space, especially if there’s not alignment. It’s very transparent. It looks disjointed and not clear.”

Leslie Berland emphasizes the importance of American Express’s collaborative team-oriented culture and how critical it is to drive social business initiatives. “I think it’s impossible to win in digital or in social media if you’re approaching it in a siloed way. And you can see it when you see different brands and companies and organizations launching things in the social media space, especially if there’s not alignment. It’s very transparent. It looks disjointed and not clear.”

However, lack of a vibrantly open and collaborative culture isn’t an insurmountable hurdle to the progress of social business. Teva, for example, operates in a highly regulated industry not necessarily known for open cultures. Yet that didn’t impede the course of their social program. “At first, people thought our internal collaboration was a finger-pointing tool that, unlike email, which is seen by a limited number of people, could expose one’s flaws or failings to many people,” says Jean-Francois at Teva.

“But when they realized it was a different mindset, they started using it extensively.” Mark McDonald, co-author of The Digital Edge: Exploiting Information and Technology for Business Advantage, goes so far as to argue that although social communities don’t require extensive structure, managers are more comfortable when social business activities are structured.

The presence of parameters, security measures and controls can ease their fears of the open-ended character of collaboration. With that comfort, leaders can take a strong role in driving a collaborative culture appropriate to the company and industry.

“But when they realized it was a different mindset, they started using it extensively.” Mark McDonald, co-author of The Digital Edge: Exploiting Information and Technology for Business Advantage, goes so far as to argue that although social communities don’t require extensive structure, managers are more comfortable when social business activities are structured.

The presence of parameters, security measures and controls can ease their fears of the open-ended character of collaboration. With that comfort, leaders can take a strong role in driving a collaborative culture appropriate to the company and industry.

If the culture isn’t open, leaders may have to stimulate collaborative behavior themselves. At a global entertainment company, for example, an operations executive wanted to build a collaboration platform for marketing departments to share information about products and promotions in real time. The marketing heads, however, rarely shared information and voiced doubt about the value of participating in a shared data platform.

To overcome the doubt and cultivate support for the idea, the executive convened face-to-face meetings with the marketing leaders. By the end of the meetings, the group had started hammering out a process for collaborating together on the project and developing the new collaboration platform.

After 18 months, they had put the protocols, processes and systems in place to capture social media data about customer reactions to various marketing campaigns across the enterprise. Insights from this collaborative effort led to the creation and adaptation of promotions and products in real time.

After 18 months, they had put the protocols, processes and systems in place to capture social media data about customer reactions to various marketing campaigns across the enterprise. Insights from this collaborative effort led to the creation and adaptation of promotions and products in real time.

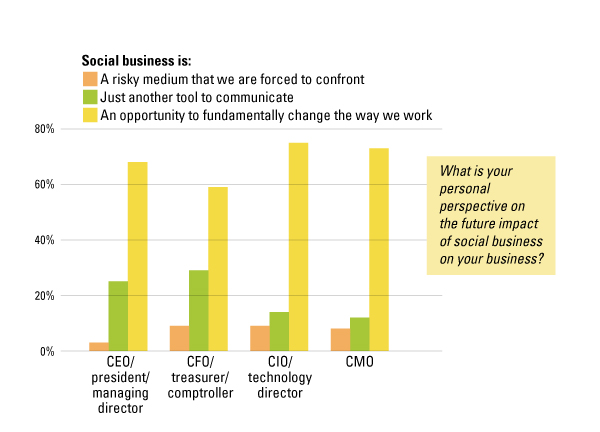

Creating collaborative behavior for social also means using it. Richard Branson of Virgin Airlines is famous for being a power user of social media. At Enterasys, Afshar and other executives actively participate in the company’s new social media channels. Without that commitment, Afshar believes social would have floundered. “It’s a fundamental equation,” he says. “No involvement by leaders, no commitment by employees. No exceptions.” (See Figure 8.)

Measuring What Matters

Although the classic adage admonishes that what can’t be measured can’t be managed, businesses on the path to social maturity aren’t letting disagreements about the “best” measures halt their progress.

While there is no consensus yet about how to measure returns from social business, some clear approaches and guidelines are coming to the fore.

While there is no consensus yet about how to measure returns from social business, some clear approaches and guidelines are coming to the fore.

Perhaps the most important: measurement must tie to what John Hagel from the Deloitte Center for the Edge terms “metrics that matter.” When seeking funding for a social initiative, for example, proposals should link the investment to what leaders are concerned about.

To make the investment case, Hagel argues that when social business improves operating performance, the improvements can be leveraged to drive broad employee buy-in and momentum — and improvements in operating metrics lift the financial metrics for which business leaders are accountable. Once leaders see that link in action, they are likely to place greater value in social tools and technologies.

To make the investment case, Hagel argues that when social business improves operating performance, the improvements can be leveraged to drive broad employee buy-in and momentum — and improvements in operating metrics lift the financial metrics for which business leaders are accountable. Once leaders see that link in action, they are likely to place greater value in social tools and technologies.

Linking social tools to operating and financial metrics poses a number of challenges. The fragmented use of social across an organization is a primary one. As Susan Etlinger, an industry analyst at the social business consulting group Altimeter, points out, “Each department has a different view on the value of the data that they are looking at.

So as a result, it requires a fundamental shift in the way that companies gather insight and normalize it across different data sets and different departments.” Professors David Gilfoil and Charles Jobs of the DeSales University business program consider the issue in their article, “Return on Investment for Social Media.” The professors developed a three-dimensional framework to align different groups of metrics. Measurement programs need to address these three dimensions:

So as a result, it requires a fundamental shift in the way that companies gather insight and normalize it across different data sets and different departments.” Professors David Gilfoil and Charles Jobs of the DeSales University business program consider the issue in their article, “Return on Investment for Social Media.” The professors developed a three-dimensional framework to align different groups of metrics. Measurement programs need to address these three dimensions:

- Levels within the organization — corporate, departmental, individual — as well as industry

- Functions impacted — for example, sales, business development, R&D

- Appropriate and available metrics — for example, sales, costs saved or website visits

A simple example illustrates how the use of social tools links to operating and financial metrics. Imagine a manufacturing company is using social networking tools to improve quality control. Social usage measures, such as relevant posts on an internal collaboration site, can be tied to operational improvements such as reducing the time it takes to resolve a quality issue. Those metrics, in turn, drive financial performance measures, including revenue increases and cost reductions.

Although straightforward applications such as these can be found in many companies, the discipline of social business measurement is still in its early stages. However, several leading experts have provided some practical guidance:

Test and Learn. Etlinger points out that Nate Silver, political analyst and author of The Signal and the Noise, sees the need for companies to embrace testing and erring when working with data. To what extent companies can embrace such an approach depends on their measurement culture.

However, even organizations without strong measurement cultures can move forward. Beth Kanter, an expert in non-profit performance measurement, stresses that companies should focus on incremental advances. Organizations launching a social initiative, for example, can start with one or two metrics tied to a business objective.

After tracking these for a period of time, the company can build momentum by steadily adding new metrics and observing patterns in the data.

However, even organizations without strong measurement cultures can move forward. Beth Kanter, an expert in non-profit performance measurement, stresses that companies should focus on incremental advances. Organizations launching a social initiative, for example, can start with one or two metrics tied to a business objective.

After tracking these for a period of time, the company can build momentum by steadily adding new metrics and observing patterns in the data.

Measurement Programs Need Continuous Improvement. In 2013, the U.S. General Services Administration released its framework and guidelines for federal agencies to measure the impact of their social media programs.

Justin Herman, social media lead at the Government Services Administration Center for Excellence in Digital Government, emphasizes that the framework is a “living document” that should be modified as new and improved ways to measure come to light. To spur the creation of those improvements, the metrics program is open not only to agencies, but also to tool developers and the public.

Justin Herman, social media lead at the Government Services Administration Center for Excellence in Digital Government, emphasizes that the framework is a “living document” that should be modified as new and improved ways to measure come to light. To spur the creation of those improvements, the metrics program is open not only to agencies, but also to tool developers and the public.

Social Doesn’t Operate in a Vacuum. Companies should not worry that social isn’t the sole, or even primary, source of improvement. Hagel points out that even if other changes occur when rolling out a social tool, if the tool was a critical enabler of the performance improvement, management should credit it accordingly.

Finally, companies should not try to measure everything. As Cisco’s Jordan cautions: “If you try to measure every single thing you are doing, you will manage the ants while the elephants are storming by.”

Creating and Curating Meaningful Content

When CARA Operations, the Canadian restaurant franchisor, wanted to bolster the morale of its wait staff and focus on customer experience, it launched a reward program through Facebook where managers and restaurant staff could congratulate others for innovative efforts beyond the call of duty.

After much planning and promotion, Staff Room was launched with great expectations — and then quickly fizzled. The problem, explains CIO Natasha Nelson, was a lack of dedicated resources to manage the program and regularly update it with new content. She says that the company thought that the program would grow organically, but “in hindsight, we see having a dedicated resource to manage the program would have helped to seed the system with the meaningful content that would have driven people to the site on a regular basis.” Having such a resource, Nelson says, would have “yielded a much higher level of adoption.”

After much planning and promotion, Staff Room was launched with great expectations — and then quickly fizzled. The problem, explains CIO Natasha Nelson, was a lack of dedicated resources to manage the program and regularly update it with new content. She says that the company thought that the program would grow organically, but “in hindsight, we see having a dedicated resource to manage the program would have helped to seed the system with the meaningful content that would have driven people to the site on a regular basis.” Having such a resource, Nelson says, would have “yielded a much higher level of adoption.”

Successful social business hinges on quality of content. And with the greater use of social comes much stronger demands for fresh, unique content. “We are entering the stage of social fatigue,” comments Ray Wang, CEO of Constellation Research. “Content has to be more relevant and in the context of a relationship, location, project and time.”

To overcome social fatigue, many companies devote considerable resources to content development. A 2013 study by Gartner, for example, found that nearly 50% of social marketing teams believe creating and curating content is their top priority. Coca-Cola is a prime example.

After becoming the first retail brand to exceed 50 million Facebook likes, Coca-Cola is shifting its marketing focus from creative excellence to content excellence — generating a steady flow of content that average social media users will feel they have to share. The goal is to create conversations with consumers by shifting from one-way storytelling to dynamic storytelling across many social media platforms.

Coca-Cola’s emphasis is on new content and applies a 70/20/10 investment principle to its creation: 70% of the content created is low-risk marketing, which consumes half their time. Another 20% feeds off ideas that already work and reinventing them to see what can be achieved. The final 10% is high-risk content marketing. When a high-risk effort pays off, it can fuel the content strategy anew.

Relevant, timely and accurate content is also paramount at Cisco and drives what the company calls its “front” — the Cisco Learning Network. Over five years, the network has grown from 600,000 to more than 2 million users. It is charged with creating the next generation of Cisco customers by providing learning tools, training resources, and industry guidance to anyone interested in an IT career through Cisco certification. The network also provides a venue for gathering and discussing the company, its product lines, and the industry overall.

Relevant, quality content is central to the network’s success, according to Jeanne Beliveau-Dunn, vice president and general manager of Learning@Cisco. Without the initial content that Cisco seeded into the system, the Cisco Learning Network would not have taken off. “The content is what separated the Learning Network from other collaboration tools such as Facebook,” she says. “The content drives an organic community toward Cisco-specific conversations.”

Given the practical reality of the community’s size, Cisco realizes that it can’t create all the content. Often, it takes the role of curator. But Cisco keeps the content fresh. “If you are trying to create community and you are lifting and shifting content, you are wasting your time,” says Beliveau-Dunn. “You don’t want to take what was stale and try to make it prettier. The key is identifying the interesting and relevant content that meets the needs of your audience and making it easy to find and digest.”

Given the practical reality of the community’s size, Cisco realizes that it can’t create all the content. Often, it takes the role of curator. But Cisco keeps the content fresh. “If you are trying to create community and you are lifting and shifting content, you are wasting your time,” says Beliveau-Dunn. “You don’t want to take what was stale and try to make it prettier. The key is identifying the interesting and relevant content that meets the needs of your audience and making it easy to find and digest.”

Changing the Way Work Gets DoneFrom responding to markets to fostering internal knowledge sharing, achieving social’s impact means changing the way work gets done. “Social is about using technology in a more thoughtful and broad-based way to meets business needs in a social context,” says Hagel. “It is front and center to the question: How can and should people connect to advance business objectives?”

Companies can change how the work is done by revamping processes and embedding social capabilities into workflows. This process — what we call social business reengineering — can break down barriers that hamper people’s ability to find the right information and work effectively across functions.

Social business reengineering is a planning process that moves systematically from strategy to technology. It begins by identifying natural groups of stakeholders who will see value in connecting in new ways — for example, linking R&D to marketers, product engineers and sales teams. With these stakeholders in mind, the process turns to the “who” and the “what” — the key players, business objectives and incentives that will garner social business buy-in and usage.

Company leaders then need to identify any barriers to adoption and have a plan in place to remove them. Once these elements have been figured out, the company can identify the most appropriate tool for the job.

Company leaders then need to identify any barriers to adoption and have a plan in place to remove them. Once these elements have been figured out, the company can identify the most appropriate tool for the job.

Dell is a prime example of social business changing the way work gets done. The company’s IdeaStorm platform is one of several initiatives where social business drives the way the company operates. In essence, IdeaStorm is a public suggestion box where customers can provide input on products and features. But the similarity ends there.

As the company listens to the market, it identifies opportunities to refine product features. It then reaches out to the customer community and works with it to identify the specific requirements. “We begin by listening,” says Richard Margetic, Dell’s director of global social media. “We then work with the customers who are most active in the conversation and drive to a product launch.”

As the company listens to the market, it identifies opportunities to refine product features. It then reaches out to the customer community and works with it to identify the specific requirements. “We begin by listening,” says Richard Margetic, Dell’s director of global social media. “We then work with the customers who are most active in the conversation and drive to a product launch.”

Companies shifting out of first gear are finding value from their social business efforts. Many realize that their companies need to be where their customers are, and they are using social business to tackle everything from sudden market shifts to the war for talent. McKinsey estimates that the global dollar worth of social business activity will be measured in the trillions. We found that executives see that value and immediacy.

Yet companies nonetheless face formidable odds. Gartner estimates that 80% of social initiatives will not meet expectations. In this report, we probed how companies stuck in first gear — or looking to boost mature efforts — can steer clear of Gartner’s prediction.

Focusing social business on business challenges is the key lesson learned. Companies that are successfully shifting out of first gear don’t view social as “an app” that will thrive at work simply because it thrives outside the office. These companies use social to address specific issues and define a role for social business in the solution. Be it tackling supply-chain issues or driving higher-octane innovation, success is about leveraging a business tool — not a technology.

Focusing on business challenges, however, is only part of the equation. To spur the effort, company leaders are cultivating new modes of communication and new patterns of dialogue. Sometimes that means modeling the behavior long before the tool is launched. Measurement is also critical.

An effective measurement mindset, however, focuses on measurement that matters. Although the discipline of measurement is evolving, successful social initiatives don’t make the great the enemy of the good. Social business success is also about generating and sustaining content. Whether it is created or curated, its freshness is the draw and the glue that holds the effort together. Finally, social business changes the way work is getting done, by reengineering processes.

An effective measurement mindset, however, focuses on measurement that matters. Although the discipline of measurement is evolving, successful social initiatives don’t make the great the enemy of the good. Social business success is also about generating and sustaining content. Whether it is created or curated, its freshness is the draw and the glue that holds the effort together. Finally, social business changes the way work is getting done, by reengineering processes.

In the time it took to read this report, millions of tweets have been posted to Twitter, tens of millions of new postings have appeared on Facebook, and thousands of hours of new video are streaming from YouTube. Social media is evolving rapidly — and that evolution is changing the face of how businesses work and compete.

Page 1. Social Business: Shifting Out of First Gear

Page 1. Social Business: Shifting Out of First Gear

No comments:

Post a Comment